Shōmyō is a form of Buddhist chant, recited by monks during rituals and ceremonies with specific melodic phrasing. Originating in India alongside the rise of Buddhism, Shōmyō traveled to China before reaching Japan in the mid-6th century. For over 1,200 years, Shōmyō has been an integral part of Japanese Buddhist practices, evolving into a unique art form that influences various aspects of Japanese music and culture.

What is Shōmyō?

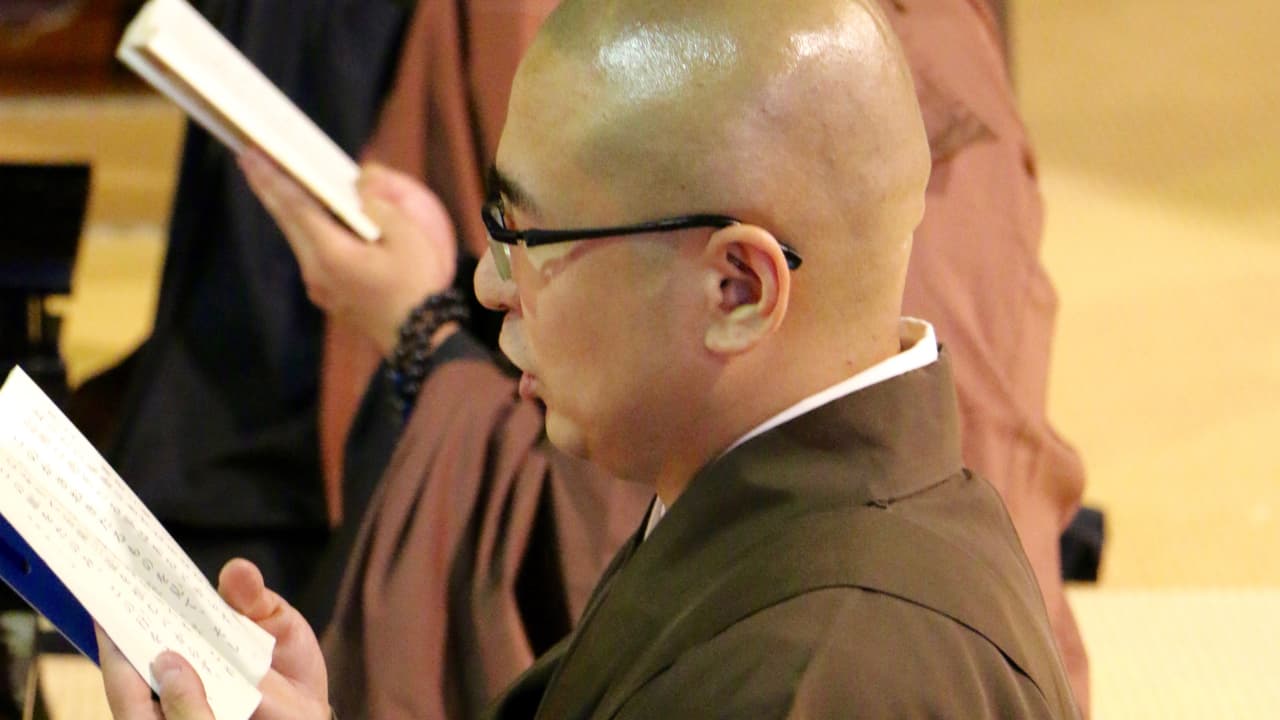

Shōmyō is a Buddhist chant with melodies that accompany sutra recitations during religious rituals. Unlike spoken sutras, Shōmyō is chanted with distinct rhythms and melodic patterns, often without instrumental accompaniment. Its purpose is to honor the Buddha’s teachings, express devotion, and guide the soul of the deceased in memorial services. The word “Shōmyō” itself refers to a sacred, melodious sound that elevates the spiritual experience during ceremonies.

The History of Shōmyō

Shōmyō was introduced to Japan during the mid-6th century, accompanying the spread of Buddhism from China. The oldest recorded performance of Shōmyō in Japan took place in 752 during the Eye-Opening Ceremony of the Great Buddha at Todai-ji Temple in Nara. From this period onward, Shōmyō became an essential component of Buddhist rituals across Japan.

During the Nara period (710–794), Shōmyō was mainly performed by monks and nobles, who studied Buddhist texts in Sanskrit and Chinese. However, as Buddhism spread to the common people during the Heian period (794–1185), a more accessible form of Shōmyō developed. Monks began to chant in Japanese, and texts were translated into the Japanese reading of Chinese characters, allowing laypeople to engage more fully in Buddhist rituals.

Famed monks such as Kūkai and Saichō, who studied in Tang dynasty China, brought back various forms of Shōmyō to Japan, establishing distinct traditions within the Shingon and Tendai schools of Buddhism. Over time, these forms of Shōmyō diversified and became more elaborate, incorporating distinct melodies that continue to be performed today.

Characteristics of Shōmyō

Shōmyō is often performed without instrumental accompaniment, relying solely on the human voice. It is typically a monophonic chant, meaning it consists of a single melodic line. The performance begins with a solo chant, followed by unison singing, where the entire group of monks joins in the same melodic phrase.

Though performed without melody instruments, the monks’ voices create a rich, resonant texture that fills the space, echoing in temples. Percussion instruments such as the hachi (cymbals) and nyo (gongs) are sometimes used to mark significant transitions in the chant or emphasize key points in the ritual.

One unique aspect of Shōmyō is its emphasis on ma (space or silence between sounds). The timing and breath control between monks are critical, as they must chant in perfect harmony. Through years of practice and repetition, monks naturally learn to synchronize their breathing and timing, creating a unified sound that reflects a deep spiritual connection.

The Development and Influence of Shōmyō

Shōmyō flourished during the Heian and Kamakura periods (1185–1333), evolving into a more musically sophisticated form of chant. It had a significant influence on other Japanese art forms, including Heikyoku (the recitation of the “Tale of the Heike”), Noh chanting, and Joruri (narrative music in Bunraku puppet theater). Shōmyō’s melodic phrasing and vocal techniques left a lasting impact on Japan’s broader musical and cultural landscape.

Today, Shōmyō is not only performed in Buddhist ceremonies but has also found a place on theater stages and in international performances, where it continues to receive high praise. Its influence extends beyond religious contexts, as it contributes to the preservation of ancient vocal traditions in Japan.

Voice as an Instrument

In many ways, the human voice in Shōmyō is treated as an instrument, used to produce complex musical phrases without the need for accompaniment. The monks’ voices resonate in harmony, creating a meditative soundscape that supports the religious atmosphere of Buddhist ceremonies. The absence of instrumental harmony emphasizes the purity of the human voice and its capacity to express spiritual devotion.

While the chanting is predominantly vocal, the monks sometimes incorporate percussive instruments like the hachi (cymbals) and nyo (gong). These instruments play a supporting role, punctuating key moments during the chanting, but the primary focus remains on the vocal harmonies created by the monks.

Conclusion

Shōmyō is a deeply spiritual and musical expression of Buddhist devotion, combining ancient traditions with vocal artistry. Over the centuries, it has grown into a unique form of Japanese religious music, influencing various aspects of Japanese culture. With its intricate vocal techniques, deep connection to breath and timing, and resonance within Buddhist temples, Shōmyō remains an essential part of Japan’s cultural and spiritual heritage.